I sat down with Ricardo Cano Mateo & Anne van Leeuwen to discuss the ways in which they think about the future in the context of their farm concept Bodemzicht. The interview was conducted on the 7th of February at Tolhuistuin in Amsterdam, this text is an excerpt from the transcript that has been edited for readability.

Sjef: When you’re considering the consequences what you want to be doing in the future, how far out are you thinking when it comes to the farm?

Anne: I think the smallest scale for me would be, 15 years?

Ricardo: Yeah, in practical terms. In conceptual terms for me, it goes beyond my life. I want to put a self-generating forest system in place that will start to express its potential after 15-20 years. After that as long as I am alive I’ll keep it rejuvenated and in productive potential. In a constant state of succession, never the same but always moving a little bit, renewing, that’s the important thing.

Once I die, complex life is going to be there. The carbon is going to be there, stored in the soil. It will then take an extreme effort to destroy this forest system. For it to become unproductive or desertified you really need to remove all the trees and everything, then plow the whole thing again.

S: You mentioned 15 years as the practical timeframe you’re looking at for the farm. On that 0 to 15 timeline, what are the instruments you’re actually using to plan ahead?

R: As frameworks for thinking, I am using three systems.

Permaculture for our farm design, in terms of establishing connections in the system, making it resilient and capturing energy.

Holistic management, for every day decision making with consciousness of our goals. What do you want to achieve and from which context are you working?

On a broader scale I’m using Yeoman’s Scale of Permanence. It’s mostly for water management, but very important for where to place elements in the landscape at a larger scale. If we are thinking about our farm then we have to think about access, locations of trees and buildings, water supply and catchment, how it all connects with our permaculture design. You could think in that same way for broader landscapes or for cities.

A: If you talk about instrumentality there’s also something very tactile about the way you read landscapes, which is sort of a landscape experience. It’s like a lens that you create to interpret landscape. Connecting the structure and ingredients, ground and plants, all these related elements create a consciousness of the different timeframe involved. That’s a very important instrument at our farm.

R: Yeah experience. Touching, smelling, tasting, experiencing, feeling, warm, cold, hard, soft. Internalizing knowledge through sensations and emotions, those experiential things are how I make connections and that, fundamentally, is the tool I use for design.

S: At a certain point this design has to express itself in the mundane and the communicable, what are the tools and media through which these ideas are expressed, even the most mundane?

R: I have a very mundane Excel sheet. It’s an extremely important tool.

S: How far ahead does the Excel sheet go? What’s the horizon of that projection?

R: It can go forever, but I am currently making a budget for 20 years. The Excel sheet is extremely useful for monitoring hard data that can go into numbers. Economics. Basically money. But the funny thing with spread sheeting is that you have to work on very predictable systems, and I am not designing very predictable systems.

S: Can you break it down a little bit? I assume you have a much better idea of what’s happening next year than in 20.

R: Yes, I’ll start for example the first years with some quick cash flow enterprises as market gardening and layers. Then I focus on very economical questions: how many eggs does a chicken lay and how much does that egg cost in the market?

I somehow have to reduce my enterprises to hard numbers to estimate an idea of the financial situation in every year. I’m taking apart all the fluctuating, difficult to predict little bits and dividing the thing into systems that I can predict to some extent, mixing those systems together. Of course at this stage there is lack of data, lack of information, lack of experience because in the end it all goes to your specific situation. So it’s very conservatively planned. I am planning thinking that every system is isolated, somehow, while I know they are not.

Excel is a very useful tool for monitoring, to not become completely crazy and philosophical about your own financial situation. It’s also very useful for communicating. You can give clear data of more or less isolated, regenerative enterprises, and you can also show how those enterprises work together in an integrated farm.

S: Are there other communicative tools that you’re using?

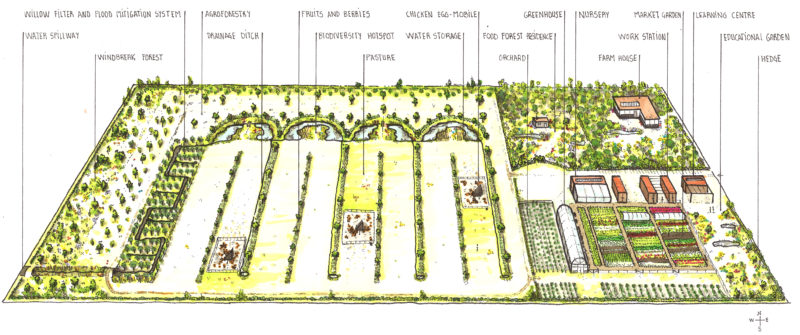

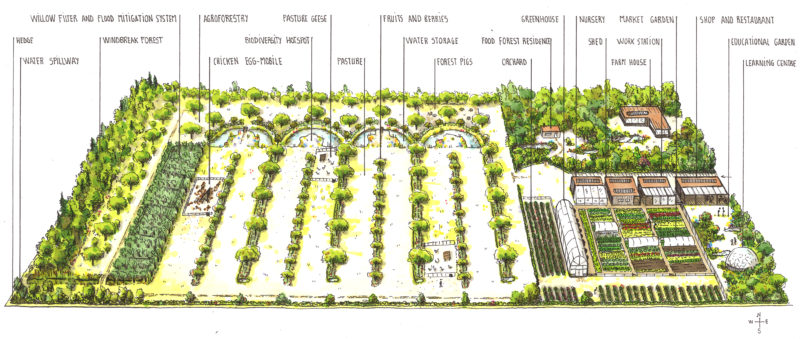

A: Mainly the plan we made. With a project like this you have an extremely broad public to deal with. You present to policy makers, but also potential investors or colleague farmers, so we try to make a plan that has all these kinds of tastes. Some people need a very literal visualization, so we made a rather corny Photoshop because this gives an almost photo-realistic impression of landscape. We also have illustrations, both technical and artistic, which for me at least works better.

R: Email is an extremely important tool, internet in general. We also do a lot of visits. So actually the car is a really important tool right now. Our network is a very important tool. It’s not so much a tool as it is capital. We are also using intellectual references a lot.

A: Yes, I’m a Latour fan for example.

S: How are you using that as a communicative tool?

A: This project is all about fundamental transition. It’s not about being organic and using less pesticides, or swapping out monocultural crops every now and then. It’s about rethinking from the ground up. How do you farm in times of climate change and biodiversity loss? It’s extremely helpful to have a fundamental framework for rethinking that. One of my ‘bibles’ is Facing Gaia, because it offers a way of rethinking our world image. Our world image of the globe is based on a very modernistic vision, and it is a very much connected to our dualistic thinking. Nature/culture, object/subject, fact/fiction. Excel categories. We are stuck in a framework that doesn’t help us to think in an integrated way. Latour’s suggestion of a Gaian worldview is much more interrelated and challenges these fundamental concepts. That really helps to translate our concept into something that is more than just a farm.

Ideally, I would like to end up not even being the owner of the farm, which is another thing. I don’t like the idea of human ownership. It could become a farm system in which the non-humans actually also have a voice in the policy-making. I would find that a very interesting, challenging model. We don’t just want to be a production farm, but a farm that helps a transition to a more integrated way of thinking, beyond either/or on many levels.

Anne & Ricardo have found a location for their farm, Bodemzicht has landed at Landgoed Grootstal in Nijmegen and will be commencing work there in 2020. You can find more news and information on their regenerative farming concept at bodemzicht.nl.